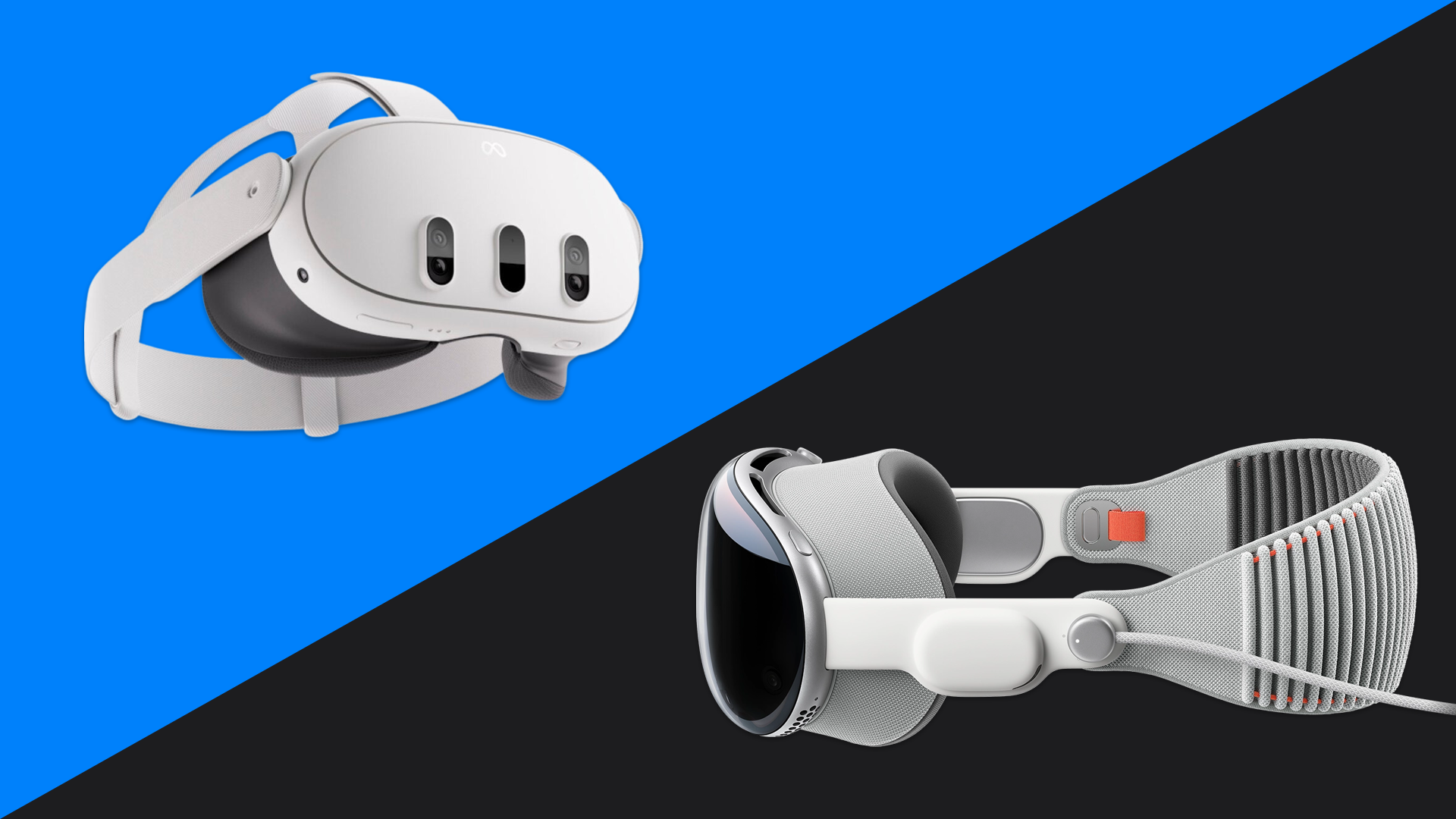

Meta is reportedly optimistic about the release of Apple Vision Pro, seeing itself as the future Android of the market. But is this thinking flawed?

The Wall Street Journal cites “people familiar with their thinking” as saying that Meta executives believe Apple’s entry into the market will “validate Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg’s gamble and draw more consumers”.

Those executives believe Meta will act as the primary competitor to Apple in spatial computing, these sources claim, playing the same role that Android does in the smartphone market today.

The week after Apple Vision Pro was announced, Zuckerberg told Lex Fridman in an interview that he saw Apple’s product as “a certain level of validation” for Meta’s significant investment in AR and VR. And in an all-hands meeting, he told Meta staff that Vision Pro’s announcement made him “even more excited and in a lot of ways optimistic that what we’re doing matters and is going to succeed”.

But there’s a huge problem with the idea that Meta will be the equivalent of Android in the XR (AKA spatial computing) market.

Android is a semi-open software platform. Any phone maker can integrate the open-source core of Android for free and without permission, and can integrate Google’s services and the Google Play Store by agreeing to certain compatibility criteria and preinstalling Google’s suite of apps.

The Meta Quest platform on the other hand is exclusive to Meta’s own devices. Its strategy is more akin to wanting to be a second Apple than what Google did with Android. That sounds more like BlackBerry than Android, and the market combination of iPhone and Android killed off BlackBerry.

Further, Google itself is seemingly preparing to be the Android of XR with… Android. Google is building an ‘Android XR’ platform to power Samsung’s upcoming headset. It will be able to bring the full Android phone and tablet app ecosystem over, something it refused for Meta, while Samsung will be able to leverage its expertise in hardware and get priority access to key components like OLED microdisplays from its subsidiaries. And while Samsung may have a period of exclusivity, that almost certainly (and reportedly) won’t last forever.

On the other hand, a major difference between the XR market and the smartphone market renders these analogies of limited use.

Meta sells its mainline Quest headsets at cost price, and sometimes even at a loss. Barring an unprecedented revenue-sharing deal that would eat heavily into Google’s profits, hardware companies like Samsung likely won’t want to compete directly with mainline Quests any time soon, especially the rumored Quest 3 Lite. Samsung’s headset will reportedly be priced somewhere around $2000.

Until it’s possible to build compelling headsets at low cost, Meta could continue its monopoly on lower-cost mass-market devices, while Apple and Google compete for a smaller market of wealthy early adopters.

But Meta’s strategy also harms its reported own long-term goal of being an Android-like player. While the company is reportedly partnering with LG for future Quest Pro headsets, no such partnerships are likely for lower-cost headsets because, again, without an unprecedented revenue-sharing deal that would eat heavily into Meta’s profits, there’s little incentive for most hardware companies to enter this subsidized segment of the market. It’s a market more akin to game consoles, where the platform holders are also the hardware providers, than smartphones,

This problem of hardware-only partners needing to make a profit in a market dominated by subsidies is arguably what killed 3DO consoles in the 90s, why so many Android phone makers exited the market in the 2010s, why the HTC Vive lost to the Oculus Rift, and why Steam Deck is a first-party device, not an ecosystem of devices as the failed Steam Machines were.

| Apple | Meta | ||

| Hardware Strategy | First-Party | First-Party | Third-Party |

| Hardware Pricing | Profit | Subsidized | Profit |

| Existing Ecosystem Integration | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

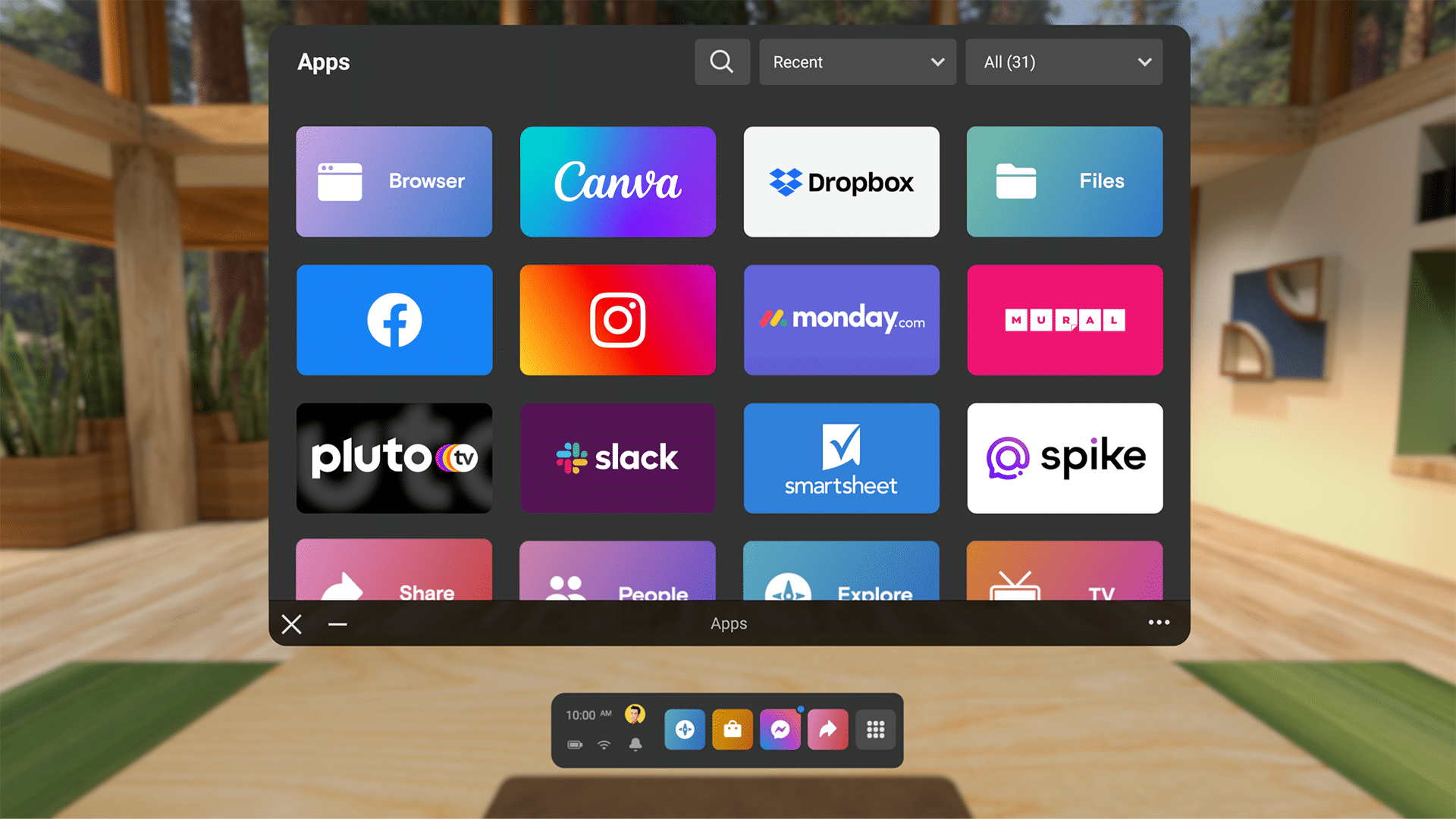

While Meta has had a 10-year lead over Apple and Google, I’d argue it has mostly squandered it. Until 2018 it was mostly focused on PC VR, a market it has mostly abandoned. And since then, it has failed to build its own software development platform besides a fragmented series of integrations for game engines like Unity, nor has it built out its own suite of vital first-party applications beyond Horizon Workrooms.

Quest today is a proven and successful games console, but Meta doesn’t have a clear path to making it a competitive general computing platform. Meta also lacks any real moat beyond its game studios. Quest headsets are powered by the same Qualcomm chipsets Samsung and others can access and use displays anyone can buy. And Google has its own world-class computer vision team.

Worse, the Quest system software and mobile app are riddled with quality and design issues. While I once expected these to be temporary teething issues in a busy time of transition in the company, that the software remains so buggy and unpolished in 2024 doesn’t inspire optimism.

The bull case for Meta is that its current software quality issues might be growing pains, solvable in coming years. Neither Apple nor Google has ever faced a well-financed vertically integrated competitor willing to subsidize hardware to push its platform. Without the ability to achieve the potential unit scale of Quest, Google’s venture could fail as consumers opt for Meta’s lower-priced alternatives with a broader range of true AR and VR content.

But the bear case is that the Quest software could remain broken as Google enters the market with a polished alternative featuring the Play Store and integration with existing Android devices and services. Alongside high-quality hardware from partners like Samsung with existing retail and marketing capital, this could render Meta as unwanted third option, the BlackBerry of spatial computing. All of Meta’s investment and research would, in this scenario, be as useful to it as Xerox PARC was to Xerox.

It’s impossible to know with certainty how the future of XR will play out. It’s even possible that new entrants ike Amazon or Valve could change the landscape entirely. But what’s clear to me is that despite tens of billions of dollars of investment, Meta’s place as Apple’s primary competitor in spatial computing is far from a sure thing, and will depend on quality of execution, not just scale of investment.