Is high-dynamic range (HDR) the key to next generation VR displays? Hands-on time with Meta’s latest demo and an interview with the head of display systems research suggests it’ll be pretty key. Read on for details.

At the recent SIGGRAPH conference in Vancouver David Heaney and I went eyes-in with Starburst, Meta’s ultra-high dynamic range VR display concept. Meta first showed the technology to Tested earlier this year as the company’s researchers outlined their goal of passing what they call the “Visual Turing Test“. For those catching up, the test refers to the idea of one day making a VR headset so advanced that people wearing it can’t tell “whether what they’re looking at is real or virtual.” Passing the test means advancing VR headset technologies along several fronts including resolution, field of view, dynamic range, and variable focus, and with Starburst showing what an ultra-bright VR headset could feel like, Meta executives are getting data that can inform them about where to target the specifications of upcoming consumer or professional-grade VR headsets.

We know Sony’s upcoming PSVR 2 headset uses an HDR display and there’s been research at companies like Valve investigating displays that were so bright you’d feel the heat of a sunny day on your cheeks — so bright in fact that one researcher called their testing equipment a “fire hazard” back in 2015. There’s actually a lot of range in exactly what “high-dynamic range” might mean. For example, the brightness of light we encounter outside coming directly from our great fusion reactor in the sky measures in the billions or millions of “nits” depending whether you’re burning out your eyeballs staring at the sun or seeing its light reflected off of everything else. Meanwhile, VR’s market-leading headset Quest 2 supplies just about 100 nits of brightness. Further, while many modern TVs feature so-called HDR displays, they typically only push out luminance measured with nits in the low thousands.

Eyes-In With Starburst

Starburst, meanwhile, tops out at 20,000 nits. With that level of brightness, Meta researchers can match the luminance of almost any indoor lighting.

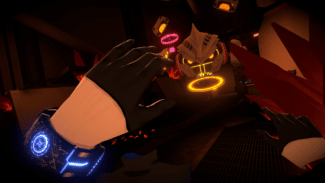

The research prototypes use off-the-shelf parts and are so heavy the headsets need to be suspended from above. You hold it to your face with hand-grips and its lenses catch the light in distracting ways. Still, looking through it provides a tantalizing tease of the future.

Meta showed two pieces of content on the headsets at SIGGRAPH. The first was the same content Meta showed Tested earlier this year — spheres floating in the open air of a studio with a bright simulated light off to the side casting across the scene. The second was a never-before-shown-in-public scene generated with a game engine on what could be an alien planet with lighting strikes, clouds, and the faint glimmer of stars in the sky.

The second scene indicates Meta is starting to explore what sort of content might be ideal for upcoming HDR displays and in our interview with Douglas Lanman, the head of display systems research at Meta, he told us that the next SIGGRAPH conference in Asia may reveal Meta’s first user studies of this technology. In our demo, the floating sphere was easily the more compelling of the two scenes shown.

You can get a rough approximation of what it’s like in the video provided by Meta above, but that video is missing the critical element of a human reaction to what you see through-the-lens. Looking at this in VR means I could place my head in just the right spot to eclipse the simulated lightbulb in the corner of the room. A halo formed framing the floating object, and then simply moving my head to either side ended the eclipse with a view straight into the light bulb. This caused my eyes to instinctively react in the same way they might when leaving a dark room and walking into one that’s very brightly lit. Essentially, I formed a sharp memory of that moment because Starburst caused me to squint from brightness for the first time in VR.

“It’s easy to predict the future when you’ve already seen it,” Lanman told us. “Can they feel that they really are present in a true physical scene? And I think if we can do that, then we’ve built the canvas we want and now we can tell any story.”

While Starburst is a wildly non-consumer friendly device, Lanman suggested that Meta openly sharing its design is meant to move forward a broader conversation in the VR community about the value of hyper-bright displays to our sense of presence inside a headset.

We’re still digesting the demos we saw at SIGGRAPH, including the first public look at hyper-realistic Codec avatars, so check back with UploadVR in the coming days as we get those articles out. Also be sure to tune into our show on UploadVR’s YouTube channel Tuesday at 10 am Pacific as we answer questions live and walk through our experiences from SIGGRAPH.