“Conflict is good for art,” says Eyal Geva, one of the three developers behind The Secret Of Retropolis.

At first, it’s not clear which conflict Geva is referring to, especially given the number of obstacles he and his team had to overcome to get their game from an early tech test to its selection as part of Cannes XR.

Peanut Button (the 3-person studio behind The Secret Of Retropolis) has overcome impossible odds, launching a game with zero budget in a temporarily converted public bomb shelter in Tel Aviv using free software and marketing tips they learned from YouTube tutorials.

“Conflict is good for us,” he tells me as he finishes his drink that VRScout organized at the Cannes Marche Du Film.

I ask Asaf, Eyal’s brother, what went through his mind on the 11th of May this year, when the bombs started falling on the team’s hometown of Tel Aviv; how he felt when the team had to run back to their HQ, which suddenly had to go back to being a public shelter for people escaping the bombings.

“I felt the same about the bunker evacuation as I did with the COVID lockdowns: These things could easily kill our game.”

Asaf then goes on to describe the tool he created for Daniel (art department) that would let him draw assets in Quill and import them directly into Unity, almost as though streamlining production pipelines and avoiding explosives are just different obstacles in VR game design that needed to be worked around.

It quickly dawns on me that Peanut Button is not a normal indie VR studio, that Retropolis is not just another VR game, and that perhaps things have changed in the world of independent VR forever.

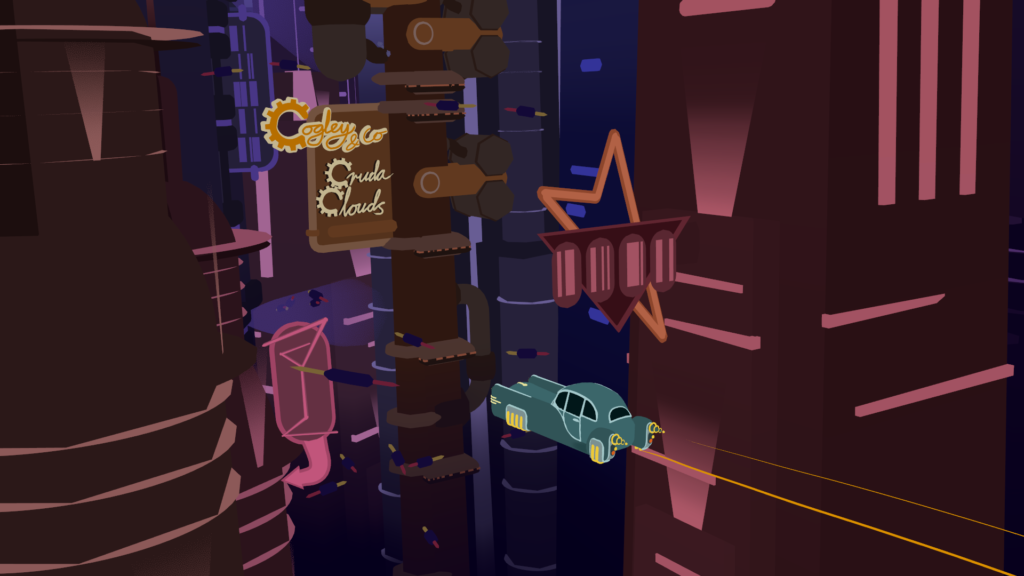

On the surface at least, The Secret Of Retropolis is a narrative VR adventure game, set in a world where robots endlessly reenact cliches from old movies and old games. You play an alcoholic detective thrown into a world of film noir intrigue and suspense. It borrows just as liberally from 1920s Italian futurism and films like The Big Sleep & Blade Runner as it does from games like Grim Fandango, The Secret of Monkey Island, and Half-Life: Alyx.

But start to unpack The Secret Of Retropolis a little further and you will find that it is more than just a series of puzzles and clever nods to pop culture. It’s a game that is a stark warning against our obsession with looking backward, even when talking about the future.

It’s a game that says something about the state of VR, and where it’s going.

“We want VR to tell meaningful stories,” continues Eyal, “The game is about the dangers of leaving things as they are. It’s a statement about the same old movies, the same old games, and the same old mechanics, our desperation in keeping the past alive; why we are we so hung up on nostalgia.”

One of the ways the game achieves this is by borrowing the gameplay mechanics of the 90s point and click adventures that Peanut Button grew up playing. As well as creating a sense of nostalgia, it also served a practical purpose in terms of production, working around the team’s limited resources.

“We started with our limitations and we built the game around them.”

The original point and click games of the 90s were born out of similar restrictions. Game designers wanted to tell stories, they wanted to give the player a sense that they were in a limitless simulation where they could do anything. However, the tools and resources at their disposal were astoundingly primitive by today’s standards. 1987’s Maniac Mansion (arguably the genre’s first breakout hit) was around 105kb in size, smaller than the size of an email today.

The solution was to trick the player into thinking they had complete freedom, using clever game design, and distracting them from the frustration of “hitting the sides” of the simulation using humor, game design, and occasionally breaking the fourth wall by having someone in the game tell you what you needed to do.

Similarly, Peanut Button has turned these limitations into design features, both the gameplay (you are fixed in one place with a limited number of items or interaction elements) and its artwork (Daniel Ho’s stunning hand-drawn style) add to the game’s stripped back, deliberate aesthetic; of being in a world that is entirely it’s own.

“The very essence of VR is about entirely escaping into a different world, into a different story,” says Daniel, “becoming the character is an incredibly important part of that… Escapism is something that humans always want, it’s not something we are ever going to stop wanting.”

By around 1998 the point & click genre had started to die. With gamers being drawn to new 3d engines, the idea of resolving complex puzzles also changed, with the internet providing an instant answer within three clicks.

What’s interesting about Retropolis picking up the genre’s baton, is how well point-and-click fits into VR as a medium. Simply being in a space and opening draws, playing with items, and speaking to people works incredibly well in VR, not to mention the fact that wearing a headset makes it hard to google “how do I solve the goat puzzle.”

In many ways the Cannes Film Festival is the perfect backdrop for them to launch their game, the festival is itself a reenactment of a bygone era: a clockwork loop of technology and nostalgia, weaving its creaky magic in an awkward dance of red carpets and flashbulbs.

The festival also has a long history of embracing new mediums and new artists (see my previous article on the festival itself), so it is perhaps fitting that Retropolis has achieved such universal praise here. The VR marketplace may still be in its infancy, but games like Retropolis are a sign that the kind of infrastructure that took the traditional gaming industry so long to develop is evolving at a surprising rate in VR.

A large part of this comes down to the new App Lab program, enabling anyone to sell their games on the increasingly lucrative Oculus Quest marketplace.

“Oculus App Lab allowed us to reach the standalone VR audience, even if it’s just the portion that checks for unofficial apps,” says Asaf.

The same shift that traditional games enjoyed a decade ago, that created the explosion of indie titles on PC and consoles, is happening right now with VR. But as ever, small studios like Peanut Button often struggle to get their game into people’s lives (and headsets).

“The biggest obstacle is the discoverability of the game on the platforms. On Steam, we’re a new studio with no previous following, and on Oculus we’re not on the official store, which means we won’t appear in any category or search…”

When I last spoke to the team, they had left the poolside cocktails and tuxedos of Cannes and were back in their bunker in Israel, diligently patching their game, working with their community, and trying to keep up with the demands that come with a successful game release.

Despite universal praise, and various offers from publishers and larger studios, they remain fiercely independent and as focused as ever on their creation.

“If you’re really passionate about what you’re doing, good people will be attracted to that and team up with you,” explains Asaf.

When I asked about a possible sequel, a second chapter, or the cliffhanger the game ends on (no spoilers), they remain as immovable as the bunker the game was written in, and as tough to crack as some of the later puzzles in their game. When probed about the possibilities of expanding the team, and the suggestion they have perhaps outgrown their bunker, Asaf remains pragmatic as always. “Even if we leave the bunker for a normal workspace, we hope that mentality won’t leave us.”

Perhaps it’s a central part of the game’s magic, to the tension that makes the teamwork so well together. After all, as Eyal says: “Conflict is good for art.”

The Secret Of Retropolis is out now on Steam and Oculus.

Feature Image Credit: Peanut Button

The post ‘The Secret Of Retropolis’: A VR Adventure Built In A Bunker appeared first on VRScout.