nDreams is a bigger deal than you realized.

I mean that quite literally; today, the studio’s headcount sits around 100 people occupying two floors of an office in the London-neighboring town of Farnborough. The team’s developed and published something like nine VR apps to date with its next, PSVR exclusive Fracked, arriving this month. It also helped Ubisoft bring Far Cry to VR arcades earlier this year, has yet more games in development, plans to publish more VR titles from indies, operates a talent-nurturing academy initiative and, just last week, announced the launch of a new, remote VR studio dedicated to making live games.

That’s quite the evolution from a once-small outfit best known for making content on PlayStation Home, and it’s taken a lot to get here.

A New Home

nDreams has been around since 2006 but you really wouldn’t know it. Its early years saw it keep a low profile between a handful of alternate reality and promotional games as well as work on Sony’s virtual social hub, PlayStation Home. When the studio dived into VR in 2013, the team had aspirations of becoming a premier studio known for making the best content you could find inside a headset. With the launch of 2020’s excellent Phantom: Covert Ops and the response to last month’s Fracked demo, you might argue the team’s well on its way to achieving that goal. But, as with many aspiring VR studios, the path towards it has been rocky.

In many ways, nDreams’ story of survival in VR is no different to many other studios. You already know the outline; VR had a slow start, making it as an indie was tough and, even with multi-million dollar investment under its belt, nDreams wasn’t immune to those struggles. Before it could get to where it is now, the team worked on a string of VR games, covering partnerships with Google, independent releases and even publishing titles from other small studios. Some tried to cater to gamers, others were more experiential. It’s an earnest, if inconsistent portfolio, connected only by the act of throwing everything at the wall to see if something might stick. Some of it did. Others? Maybe not so much.

Chief Development Officer, Tom Gillo, who joined the studio in 2015 after working on the PSVR experiences that would eventually make up PlayStation VR Worlds at Sony London Studio, puts it in a way that will ring true for many long-time VR developers: “I guess the thing, that we tried to do quickly and early on in our journey, was unpack what we felt made good VR. So it was really understanding the tent poles around, how we would try and make the best VR games that we could. And, you’ll know this, it’s not always possible on some of the budgets, it’s a challenge.”

Some Assembly Required

Reluctantly waving goodbye to the steady stream of revenue it generated making content for PS3’s PlayStation Home (Sony didn’t carry the service into the PS4 era), nDreams searched for what’s next. In the very early days of VR, it released the SkyDIEving demo for the first Oculus Rift development kit. It was one of the first playable experiences for the device and proved popular enough that people near the offices even asked if they could come in to see it (I know this because, anecdotally, I have friends working in completely different industries that did just that).

Following up were early titles for the first edition of the Gear VR, including a space shooter called Gunner and a virtual beach destination simply known as Perfect Beach. The former was essentially EVE Gunjack, with gaze-based aiming, whereas the other dipped its toes into the still-untapped potential of virtual tourism. But these experiments were secondary to what the team hoped would be its breakout VR game, a narrative-driven launch window title for all upcoming VR platforms named The Assembly.

I’d be willing to bet that, for a lot of you, that name doesn’t ring a bell.

Not that The Assembly was bad. Far from it, in fact; The Assembly was intended to be an answer to the call for ‘real’ VR games, featuring an intriguing universe in which players explored the underbelly of a sinister scientific organization. It boasted great production values for VR at the time and had a focus on keeping players comfortable. But the game had started work in 2014, a year before the reveal of the HTC Vive, and it would eventually launch on PC in July 2016, a good few months before the arrival of PSVR and the Oculus Touch controllers. As such, nDreams had stuck to its guns and developed a gamepad-only control system for the experience.

That’s why you probably don’t recall the game among other breakthrough titles from 2016 like Job Simulator and Superhot, which placed a huge emphasis on motion controls. Comparatively, The Assembly was an ironic case of feeling dated even as it launched on futuristic hardware. It did eventually get motion controller support of its own, but the game’s 2014 foundations limited just how far interaction could go. “I think like any like any studio going through that journey and particularly at that time with the hardware being so in its infancy, clearly you’re going to learn lessons from it,” Gillo says. “And one of the lessons I guess, would be that […] we need to now figure out how to be even better, and the signature things we need in VR games.”

It also taught the team the realities of where VR was going in its first few years. Gillo says nDreams views The Assembly as a success and that it did see “very long tail sales”. But it was also self-published in the hopes that it could help fund future solo efforts from the studio. “Unfortunately, the market just wasn’t there, in terms of the numbers to make that viable.”

It’s Dangerous To Go Alone

The Assembly was a learning experience, then, not just about how to make VR games but also what nDreams was going to need to do in order to survive in these nascent years. It would need to apply the latter before it could really return to the former; the studio wouldn’t take another stab at an ambitious single-player narrative adventure until Phantom: Covert Ops four years later, but it released four titles in the meantime. There was Perfect, another VR travel and relaxation app that simply presented a handful of nice environments to stand in. Gillo says this was an exercise in “understanding how we could get something to market relatively quickly and how we could lean into some of the early adopter expansion.”

Gaming-wise, nDream’s output was mixed. There was Danger Goat, a Google Daydream exclusive puzzle title that, while fun, really didn’t have much to offer the medium. Gillo fondly recalls getting to be one of the first to work on Daydream and laments its downfall but isometric puzzle games about secret agent goats weren’t exactly what the VR audience was clamoring for in 2017. nDreams also got into VR publishing with Bloody Zombies, a 2D beat ’em up which, while certainly competent, didn’t really seem well suited for the platform either.

This, I’d argue, wasn’t the sort of output you might expect from a team that wanted to be making VR’s biggest games. But, can you blame them? If Google is dangling money to make a game at a time when self-publishing your own is financial suicide, Danger Goat probably seems like a safe bet. “I think we’ve always aspired as a studio to do longer-form games,” Gillo responds when asked if the studio was where he thought it would be in that era. “But there is obviously the reality of the market and the reality of the budgets available and so on. And so you work with what you have to continue to elevate your capability and your understanding of that market.”

A Fruity Twist

At this point, we’re reaching 2018, a time in which the VR market seemed pretty bleak. Sony’s PSVR seemed to be selling somewhat respectably, but the barriers to entry for PC VR — cost, hardware and accessibility — were proving too big to significantly grow the install base. Once-bright-eyed and hopeful developers were beginning to throw in the towel. Without a major hit to its name, you might’ve suspected nDreams to follow suit. And maybe something would have been different were it not for Shooty Fruity.

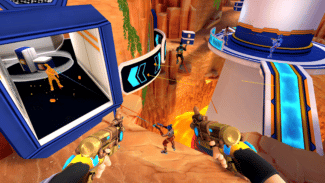

Released in mid-2018, this was a wave shooter that, again, might not have resembled the industry-defining experience nDreams had envisioned itself making but would help it get there thanks to, in Gillo’s words, being “phenomenally successful” from a sales perspective. This was before we had the Oculus Quest (the game didn’t hit that platform until 2020); Shooty Fruity managed to resonate with VR’s existing userbase.

It was a simple if strange idea; you shot sentient fruit as you pushed supermarket items through a checkout. Truthfully I remember being a little vexed when I first saw it that year, and we only ended up giving the game a 6/10. But I distinctly recall the buzz online around launch being quite positive, particularly on PSVR where shooter fanatics were hungry for something new. Though full sales stats for Shooty Fruity haven’t been revealed, Gillo’s tone suggests the game’s reception helped open a few doors.

And that’s a key point. From Gunner through to Danger Goat, nDreams hadn’t yet really had a standout VR hit. While developers like Sanzaru Games were scoring exclusivity contracts with Facebook and the like, nDreams seemed to keep being passed up on to make its own Asgard’s Wrath or Lone Echo. “I think one of the things that I realized really early on, and this is slightly hubris and naivety on my part, is that you come from somewhere like London Studio and then you come to nDreams, then you just assume that the world’s going to take note,” Gillo says. “And that was tough because, we were hiring some really brilliant people, seasoned veterans from elsewhere around the industry. But if you’re Mr. Oculus or Mr. Sony, you’re just going to judge us on the last title.”

Out Of The Shadows

With Shooty Fruity’s success and a proven record of putting out multiple games, nDreams hoped it had reached that point of notoriety. It was now time to “bet the farm”, in Gillo’s words, on the kind of ambitious, long-form VR experience the team had always wanted to make. Internally, the studio had been working on a prototype for a different kind of stealth game. You wouldn’t be performing close-range takeouts like Solid Snake or donning Splinter Cell’s green goggles; you’d be sneaking through an enemy base through water, set entirely within a kayak. All your weapons would be attached to you and handle realistically, while movement with the paddles would feel immersive and authentic. This was to be a VR game that wouldn’t make any compromises in its quest for presence. Gillo says it was crucial to show that demo to the right people.

“And it was great because we got the reaction that we hoped we would, which is, ‘Wow, this is, this is really unique and it’s thinking about VR, in a really innovative way’,” he says. “And so that was the sort of pivotal moment really where we knew we were onto something and we could yet springboard from there.”

Phantom ended up being published by Facebook itself, launching on Oculus Quest and Rift in mid-2020. It achieved the highest score Upload had given an nDreams game to date thanks to its compelling, immersive mechanics, and still ranks on our best stealth games list. It wasn’t perfect but, by a lot of VR design standards, it set an incredibly high bar. Earlier this year, nDreams confirmed that the game had generated more than $1 million in revenue. Again, perhaps not quite the blockbuster numbers a team of nDreams’ size (which by this point was approaching 100 people) would need if it self-published the game, but a sign of significant progress. Finally, nDreams was making the games it had envisioned when it started its VR journey nearly a decade ago.

“When I have a down day, I will go and I will read comments on the Oculus store about Phantom and occasionally you’re going to get somebody for whom it didn’t quite resonate,” Gillo says. “90% of the time it’s people just going ‘I absolutely love this’ and it warms the heart because you go, ‘Okay, great. It did resonate. And it did land and people did get what we’re trying to do.’ ”

Frack To The Future

Given that Phantom was such a considered effort on the immersion front, it’s somewhat surprising to see the studio throw so much of its design out the window for its next game.

Earlier this month, Creative Director Steve Watt told me that immersive design wasn’t a big focus for Fracked. The game instead wants to cater to explosive AAA action more akin to a Call of Duty or Uncharted title. It’s a bombastic shooter in which players shoot down ski slopes and charge through combat arenas, with more in common with Doom than the studio’s last effort. “So there’s lots of things where the medium has moved forward and where we’re actively pushing against [boundaries], sensible or not,” Gillo says of the change in tone. “You know like deliberately pushing to find out what is acceptable. And I think that’s always really important in any medium and art form is that you continue to push, continue to explore and you consider what works well.”

Something like eight years on from when it first jumped into VR then, nDreams has a sense of getting there. There’s a busyness to the studio’s office, the sensation of many different parts moving a mile a minute, and the team’s new Orbital studio will see it cater to a different branch of the VR market with a focus on live games (titles that evolve post-launch with new in-game content, like it Fortnite or mobile apps). “I’m thinking about, the kinds of audience expectation in five years’ time,” Gillo says of the expansion. “And yeah, I think that does mean much much longer engagement. That means different ways of delivering content. And that’s not something that we’ve invested in enough. We’ve done things here, obviously we supported our titles, but service games is a different skill set. And so by building that out and putting a slightly different lens on things, it gives us learnings again.”

nDreams survived VR’s shaky start and now more closely resembles the studio its leaders had dreamed of it becoming. Like any long-running VR developer, it hasn’t been easy, but it also helped the team rack up lessons applicable to the next phase of VR.

Gillo ends on this note: “I can’t really talk about what’s coming next, but the things that we’re working on internally now are the things that, if I could have gone back five years and said, ‘Hey, you’ll be doing this’, then it would have made the journey all worthwhile? The answer is, wholeheartedly: Yes.”