24 hours before I was set to publish my Half-Life: Alyx review, I found myself in a sudden crisis of confidence.

I’d just turned in my near-3,000 word draft. In it, I’d outlined a game that easily earned full marks for its standout production and refined gameplay, but was curiously measured in other areas. It was disappointing, I argued, that Alyx didn’t let players get their hands a little dirtier. Valve kept a lot of the game’s physicality — namely the melee attacks and fully-interactive environments that made Boneworks and The Walking Dead: Saints & Sinners shine — at a knowing arm’s length. Alyx seemed visibly weary of taking that step.

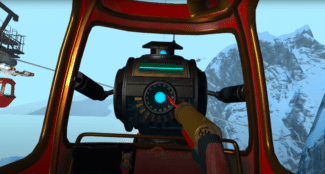

Then Valve tweeted this:

When Half-Life: Alyx arrives tomorrow, we know many of you will want to share your first playthough with friends, so we’ve published a guide to help tune the game’s settings for spectating and streaming before you start. https://t.co/4RS3FytHMD pic.twitter.com/2qlgof0zr7

— Valve (@valvesoftware) March 22, 2020

This GIF gave me pause for concern. I’d played through Alyx three times now (including on the hardest difficulty) and not once had to fight off headcrabs with my own two hands and certainly not with the aid of an office chair. Had I somehow played it wrong? Did Alyx actually hide a deeper level of physical action that it just wasn’t communicating very well?

Not really, I don’t think. I did another half-run of the campaign and came to the same conclusions I had the first three times – some props in certain scenes were still plastered firmly in-place, like a ladder I had first thought would help me clear the gap Alyx must jump in the opening escape sequence.

Then I bravely tackled the sewer section once more, this time arming myself with a giant plastic bucket in hopes that I might be able to scoop up headcrabs, trap them inside and then pin the makeshift cage to the floor with a heavier item. No such luck – if the bucket didn’t catapult itself to the other side of the room in stubborn defiance of my demands, the headcrabs themselves often refused to be caged. It doesn’t help that you can’t pick up live crabs in the same way that makes toying with Boneworks’ robotic counterparts such a joy.

Ultimately I decided not to let this weigh too heavily on my review as it seemed unfair to a game that hadn’t explicitly promised this approach and that I myself was forcing the Boneworks comparison on it heavy-handedly. And, as a result of that design, Alyx avoided some of the messiness its contemporaries chose to embrace. But, one year on, I can’t shake the suspicion that Alyx could have pushed the bar for VR even higher than it already has done if it had leaned into these concepts a little harder. What if Valve thrust you into situations in which you used garbage bin lids as a primitive means of cover as you charged The Combine in the game’s firefights? How much scarier would that hotel headcrab onslaught have been if all you’d had to defend yourself with was one end of a mop?

In fairness, Valve’s Jason Mitchell gave solid reasoning when I asked about this direction ahead of the game’s release:

“In Alyx if we have the player hold something large and rigid there’s a lot that’s gonna happen in a physical simulation that’s not gonna feed back into your hand,” he said. “So basically you’re not going to have any kind of haptic feedback. Don’t even worry about bludgeoning and impaling something, even something just as simple as tapping a tool on a desk or whatever. You don’t get the force feedback from that sort of thing. I think it’s just inherent in VR that we aren’t in the sci-fi future exoskeleton level of VR where every bit of our sensory input and output can be manipulated. So it’s not a strength of VR systems now, so we decided not to lean into it for that reason.”

It’s a sound position and, if Valve had decided otherwise, we might not even be talking about the same game right now. Regardless, these omissions are what made Alyx a strangely familiar experience for long-time VR players. A handful of sequences aside (Chapter 7, to be precise), it rarely feel as revelatory as the moment you swing a katana through a zombie’s neck in Saints & Sinners, or surpassed one of Boneworks’ platforming puzzles not by playing to the game’s rules but instead those you’d expect from our reality.

Standing in for those revelations, though, was rock solid playability. Let’s be clear, this is not intended to trivialize Valve’s work on Alyx, a game that, on its first birthday, has more than fulfilled its duty as a touchstone of quality VR gaming. In place of these interactions was peerless level and enemy design, something that both Boneworks’ single-minded AI and Saints & Sinners repeated open-world environments can’t quite measure up to. And, while it might not have had much in the way of melee combat, rooting yourself behind cover and daring to poke out behind corners or steal pot shots from under cars remains a must-see experience.

There’s still ground to cover, too. Essential as it is, for many Alyx alone won’t justify dropping around $1,000 on a gaming PC and compatible VR headset. But the prospect of the game potentially coming to Sony’s now-confirmed PS5 VR headset is a tantalizing one indeed, and it may well be here that the game truly earns the moniker of a system seller. I won’t join the chorus of speculation about what Valve itself has planned in the future, suffice to say that I hope the game’s ending moments are a direct hint that its next VR efforts might further bridge the gap between my hopes and VR’s capabilities.

A year ago today I had this to say about Alyx: “Half-Life: Alyx makes good on its second chance, it is as essential a VR game as you’ll find in 2020, but perhaps the most exciting thing about it is the message is that the best is yet to come.” On the game’s first anniversary, it’s that ‘best’ part I find myself thinking about most. Half-Life: Alyx set a bar yet to be matched by any other VR game, of that there is no question. But I’m still dreaming about what remains just out of its reach.